Physical Therapy Guide to Bell's Palsy

Bell’s palsy is a form of temporary facial paralysis that can affect a person’s daily function, communication with others, self-esteem, and quality of life. It occurs when the nerve that controls movement on 1 side of the face becomes inflamed. Bell’s palsy usually begins with a sudden feeling of weakness or paralysis on 1 side of the face.

CAUTION: These symptoms also can indicate a severe condition, such as a stroke. IF YOU EXPERIENCE ANY TYPE OF FACIAL WEAKNESS, SEEK MEDICAL CARE IMMEDIATELY! Call an ambulance if the weakness is accompanied by:

- Pain in the ear, cheek, or teeth.

- Loss of facial sensation.

- Confusion.

- Weakness of arms or legs.

- Vision changes.

- Fever.

- Headache.

Physical therapists are movement experts. They improve quality of life through hands-on care, patient education, and prescribed movement. You can contact a physical therapist directly for an evaluation. To find a physical therapist in your area, visit Find a PT.

What Is Bell's Palsy?

Bell’s palsy is a form of temporary facial paralysis that can affect a person’s daily function, communication with others, self-esteem, and quality of life. It occurs when the nerve that controls movement on 1 side of the face becomes inflamed. The condition often comes on suddenly, causing varying degrees of facial weakness, but begins to recover naturally.

In 70% of cases, patients with complete facial paralysis (and 94% of patients with partial paralysis) recover within 6 months. However, 30% of patients do not recover completely.

Although the cause of Bell’s palsy remains unclear, it is thought that some cases might be caused by the herpes virus. Other risk factors include: pregnancy, obesity, chronic high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, upper respiratory infections, and severe preeclampsia (a complication of pregnancy).

Facial weakness or paralysis also may be caused by several other conditions including trauma, a congenital (present at birth) condition, surgery, or tumors.

How Does It Feel?

Bell’s palsy usually begins with a sudden weakness on 1 side of your face or a sudden feeling that you can’t move 1 side of your face.

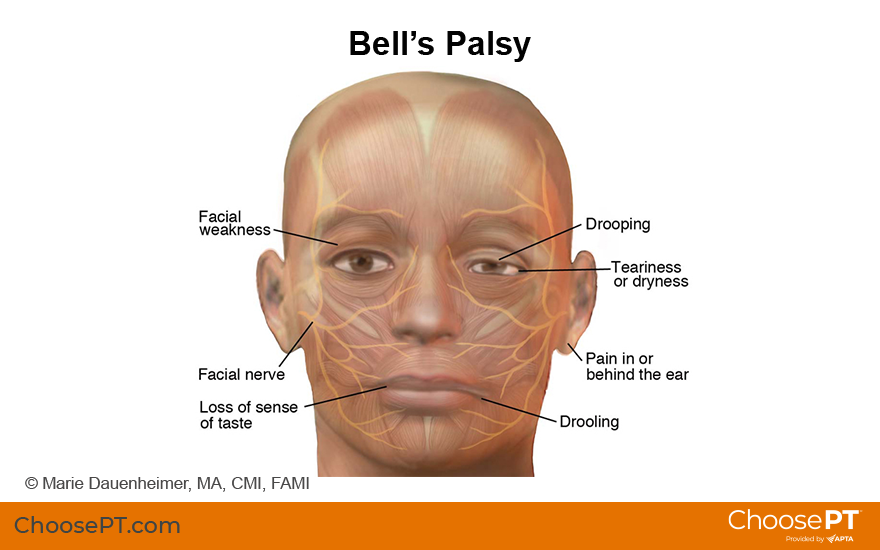

Bell’s palsy can worsen quickly. Other symptoms may include:

- Inability to close the eye on the affected side

- Drooping of the affected side (within a few hours to overnight)

- Teariness or dryness of the affected eye

- Pain in or behind the ear on the affected side

- Sensitivity to sound

- Drooling

- Loss of the sense of taste

- Difficulty speaking due to weakness around the mouth

How Is It Diagnosed?

Diagnosis of Bell’s palsy will often involve your doctor observing your facial movements such as blinking your eyes, lifting your brow, smiling, and frowning, among other movements.

The examining physician may additionally recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for an individual with facial weakness or paralysis to rule out more serious conditions such as a tumor or stroke. Once testing has ruled out other possible conditions, the physician will likely diagnose Bell’s palsy, and recommend treatment by a physical therapist.

People diagnosed with Bell’s palsy often receive a course of steroid medication to reduce the swelling around the nerve that controls the movement of the face. In some cases, individuals are given an antiviral medication as well. Your physician will provide a referral for physical therapy.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

In the first couple of days to a week after symptoms start, your physical therapist will evaluate your condition, including:

- Review your medical history, and discuss any previous surgery or health conditions

- Review when your current symptoms started and what makes them worse or better

- Conduct a physical examination, focusing on identifying the patterns of weakness that are caused by Bell palsy:

- Facial movements of the eyebrow

- Eye closure

- Ability to use the cheek in smiling

- Ability to use the lips in a pucker

- Ability to suck the cheeks between the teeth

- Raising the upper lip

- Raising or lowering the lower lip

Your physical therapist will immediately:

- Educate you about how to protect your face and your eye

- Show you how to manage your daily life functions while you have facial paralysis

- Explain the expected path to recovery, so that you will know the signs and symptoms of recovery

- Evaluate your progress, and determine whether you need to be referred to a specialist if progress is not being made

The first priority is to protect your eye. The inability to completely and quickly close your eye makes the eye vulnerable to injury from dryness and debris. Debris can scratch the cornea—the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and front chamber of the eye—and could permanently harm your vision. Your physical therapist will immediately show you how to protect your eye, such as:

- Using self-made and commercial patches

- Setting a regular schedule for refreshing eye fluids

- Carefully closing the eye with your fingers

If you have partial facial movement, your therapist will teach you a few general facial exercises to do at home. These exercises will help you learn to move the weak side of your face and help you use both sides of your face together. One of the exercises is a gentle blowing action through your lips.

During Recovery

Your physical therapist will help you regain the healthy pattern of movements that you need for facial expressions and function. Recovery can be challenging because:

- Normally, the ability to make facial expressions and many facial movements is "automatic";—that is, you're born with this ability and never had to think about it before

- Unlike other muscles in your body, the facial muscles do not have sensors that tell your brain all of the necessary "details" about how to move

Your physical therapist will be your coach throughout this challenging time, guiding you through special exercises that are designed to help you relearn facial movements based on your particular movement problems. Your exercises may change over the course of recovery:

"Initiation" exercises. In the early stages, when you might have difficulty producing any facial movement at all, your therapist will teach you exercises that cause ("initiate") facial movement. Your therapist will show you how to position your face to make it easier to move (called "assisted range of motion") or how to "trigger" the facial muscles to do what you want them to do.

"Facilitation" exercises. Once you're able to initiate movement of the facial muscles, your therapist will design exercises to increase the activity of the muscles, strengthen the muscles, and improve your ability to use the muscles for longer periods of time ("facilitate" muscle activity).

Movement control exercises. Your therapist will design exercises to:

- Improve the coordination of your facial muscles

- Refine your facial movements for specific functions, such as speaking or closing your eye

- Refine movements for facial expressions, such as smiling

- Correct abnormal patterns of facial movement that can occur during recovery

To work on coordinating your facial muscles, you'll need to have a sufficient level of activation of facial muscles first. Your therapist will determine when you're ready.

Relaxation. During recovery, you might have facial spasms or twitches. Your physical therapist will design exercises to reduce this unwanted muscle activity. The therapist will teach you how to recognize when you are activating the facial muscle and when the muscle is at rest. By learning to contract the facial muscle forcefully and then stop, you will be able to relax your facial muscles at will and decrease twitches and spasms.

After Recovery

Some people might have greater difficulty moving their face after a period of improvement in facial movement, which can make them worry that the facial paralysis is returning. However, the recurrence of facial paralysis of the Bell Palsy type is uncommon.

New difficulty in moving the face is more likely the result of increasing the strength of the facial muscles without improving the ability to coordinate and control the movement. To keep this from happening, your physical therapist will show you what facial movements you should avoid during recovery. For instance, the following might lead to abnormal patterns of facial muscle use:

- Trying to make the biggest facial movement or muscle contraction that you can, such as smiling as much as you can

- Chewing gum with great force

- Blowing up a balloon with all of your effort to work the facial muscles

Your therapist will coach you to use your face as naturally as possible, without trying to restrict facial expressions because they look "different."

What Kind of Physical Therapist Do I Need?

All physical therapists are prepared through education and experience to treat conditions or injuries. You may want to consider:

- A physical therapist who is experienced in treating people with neurological problems. Some physical therapists have a practice with a neurological focus.

- A physical therapist who is a board-certified clinical specialist or who completed a residency or fellowship in neurologic physical therapy has advanced knowledge, experience, and skills that may apply to your condition.

You can find physical therapists who have these and other credentials by using Find a PT, the online tool that built by the American Physical Therapy Association to help you search for physical therapists with specific clinical expertise in your geographic area.

General tips when you're looking for a physical therapist (or any other health care provider):

- Get recommendations from family and friends or from other health care providers.

- When you contact a physical therapist for an appointment, be sure to ask about his or her experience in helping people with Bell palsy or facial paralysis.

- Be prepared to describe your symptoms in as much detail as possible, and say what makes your symptoms worse.

The American Physical Therapy Association believes that consumers should have access to information that could help them make health care decisions and also prepare them for their visit with their health care provider.

The following articles provide some of the best scientific evidence related to physical therapy treatment of Bell's palsy. The articles report recent research and give an overview of the standards of practice for treatment both in the United States and internationally. The article titles are linked either to a PubMed abstract of the article or to free full text, so that you can read it or print out a copy to bring with you to your health care provider.

de Almeida JR, Guyatt GH, Sud S, et al. Management of bell palsy: clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 2014;186(12): 917–922. Free Article.

Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines: Bell’s palsy executive summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(5):656–663. Free Article.

Murthy, JM, Saxena AB. Bell’s palsy: treatment guidelines. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14(Suppl 1):S70–S72. Article Summary in PubMed.

VanSwearingen J. Facial rehabilitation: a neuromuscular reeducation, patient-centered approach. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24:250–259. Article Summary on PubMed.

Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1598–1607. Article Summary on PubMed.

Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;549:4–30. Article Summary on PubMed.

Diels HJ. Facial paralysis: is there a role for a therapist? Facial Plast Surg. 2000;16(4):361–364. Article Summary in PubMed.

Brach, JS, VanSwearingen, JM. Physical therapy for facial paralysis: a tailored treatment approach. Phys Ther. 1999;79:397–404. Article Summary on PubMed.

VanSwearingen JM, Brach JS. Validation of a treatment-based classification system for individuals with facial neuromotor disorders. Phys Ther. 1998;78:678–689. Article Summary on PubMed.

Diels, JH, Combs D. Neuromuscular retraining for facial paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1997;30(5):727–743. Article Summary in PubMed.

Ross B, Nedzelski JM, McLean JA. Efficacy of feedback training in long-standing facial nerve paresis. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(7 Pt 1):744 –750. Article Summary on PubMed.

*PubMed is a free online resource developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PubMed contains millions of citations to biomedical literature, including citations in the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database.

Expert Review:

Jul 21, 2017

Revised:

Sep 20, 2017

Content Type: Guide

Bell's Palsy

PT, PhD

The editorial board